How a momentary encounter became the first photographic portrait

Our normal expectations of photography tend to focus on the instancy of the process. A Photo is a snapshot, a frozen slice of time measured in fractions of a second.

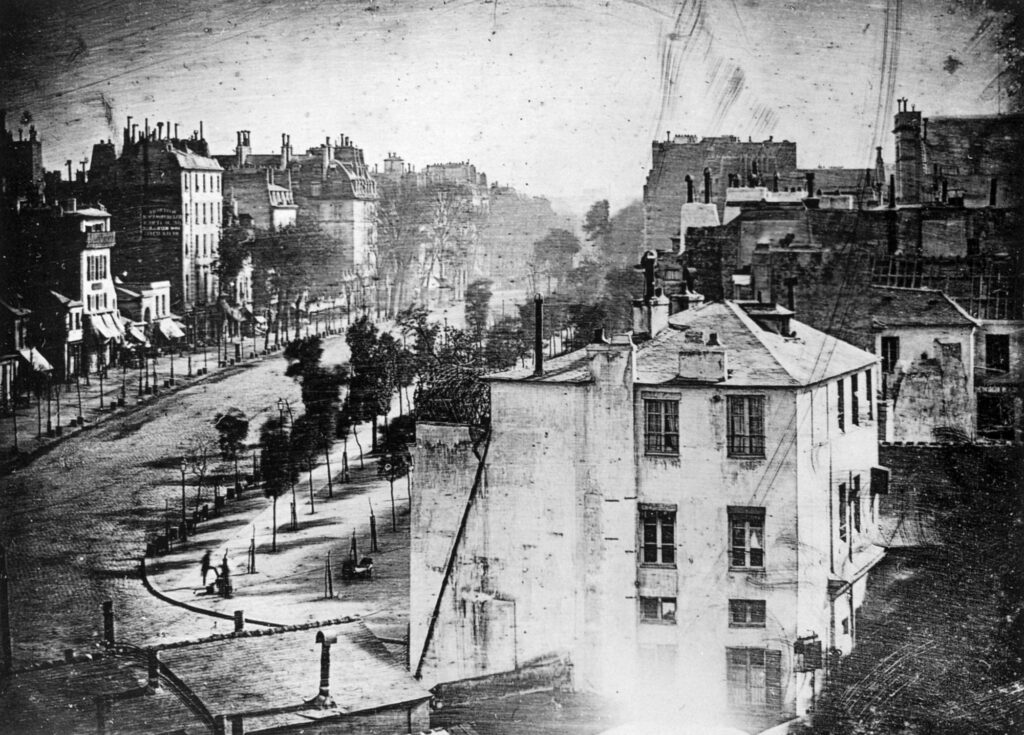

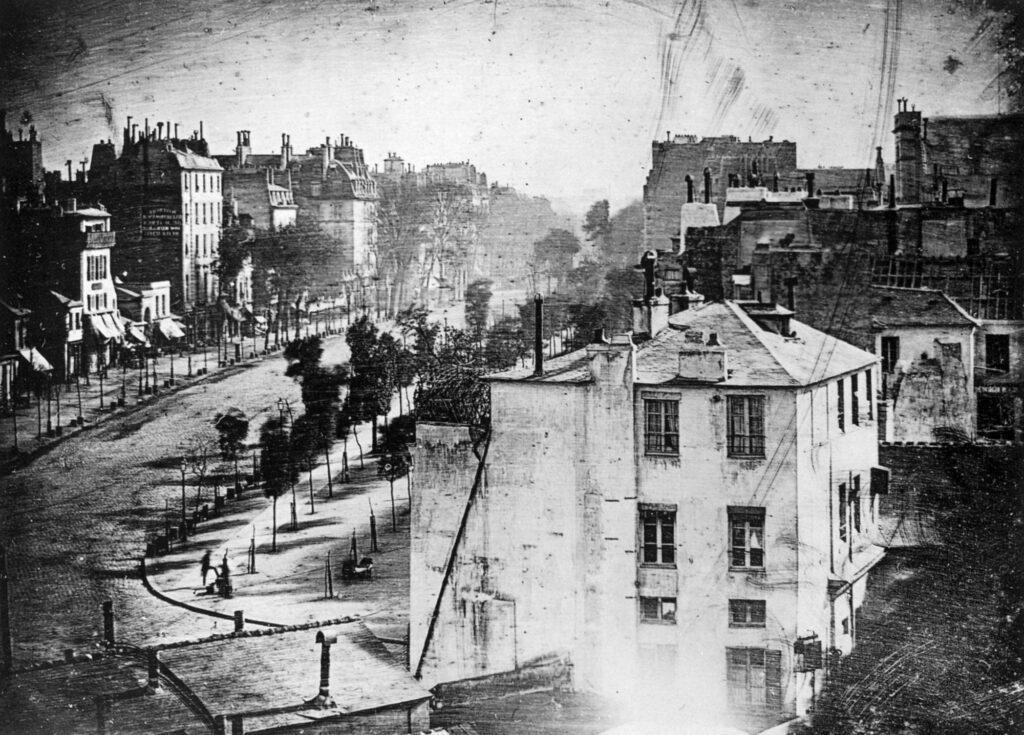

This particular photograph is different. It was made over a much longer duration. Look to the bottom-left of the frame. There is a man having his shoes shined. That man — this picture — is the earliest known photograph of a recognisable human being. It was taken in Paris, France, in 1838 by Louis Daguerre.

It wasn’t that the man in question was the only person on the street. More than likely, the street was full of horses and carts and pedestrians going about their business. It was rather that the exposure time for the image was around ten minutes, which meant that everything else in the scene was moving too fast to be captured in any clarity.

Only the man with his leg raised, who stood still long enough to register in the photograph, is at all visible. The shoe-shiner working on his shoes is also present, although his form is not as distinct.

I can’t help but wonder what it was the man was thinking at the time. It is perhaps an insight that only imagination can supply: a man from two centuries ago stands in the middle of a busy Parisian street having his shoes cleaned for the duration of ten minutes. What was he thinking about as he stood there? I’d love to try to answer that question some time.

The Advent of Photography

The invention of photography required certain technologies to come together to complete the jigsaw. One component had been around for many centuries: known as a camera obscurer, this was a piece of apparatus that projected an image of a scene onto an interior screen of a darkened room or box. It had been used by artists like Johannesburg Vermeer, so the images could be accurately traced and used as a basis for painting. The resulting projection was in fact reality seen in reverse, as one sees oneself in the mirror.

The component of photography that was missing was a means of fixing the projected image to a surface. That is, until the early 18th century when it was discovered that silver salts – otherwise known as silver halides – were sensitive to light.

The first photograph using a camera obscura was made by the French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, who used a lithographic stone coated with bitumen, a light-sensitive substance, to capture his image. It is estimated that the exposure time for Niépce’s first photographs was anywhere between eight hours and an entire day.

Louis Daguerre and his Daguerreotype

In 1837, Louis Daguerre successfully used a chemically-treated copper sheet to register a photographic image. He called it a daguerreotype.

Once the plate had been exposed to light in the camera, the image that sat latently within the coating of light-sensitive silver iodide was developed and fixed by a combination of mercury vapour and warm salt solution.

Once the plate had been exposed to light in the camera, the image that sat latently within the coating of light-sensitive silver iodide was developed and fixed by a combination of mercury vapour and warm salt solution.

Daguerre took photos of objects first, creating still-life images of plaster casts and other objects residing in his workshop.

(Daguerre was also celebrated theatre designer as well as an inventor, which explains the plaster casts.)

Some time in late 1837 or early 1838, Daguerre turned his camera towards the street outside and captured the image of the man having his shoes shined. The view was along the Boulevard du Temple in Paris, a fashionable area of shops, cafés and, most especially, theatres – which is presumably why Daguerre had his workshop in the district. The Boulevard du Temple was also known as the “Boulevard du Crime” on account of all the dramatic depictions of murders that were a favourite among theatre goers at the time.

It is, in my opinion, a very beautiful photograph – irrespective of its unique historical significance.

I like the way the central subject of the image is the large, white, somewhat unremarkable building directly in front of us. It is slightly angled, so that the viewers eye is gently pushed left-wards. I find my gaze peeling left, around the bend in the road and up the boulevard. The canopies of shop-fronts catch my eye, and the line of trees receding into the distance. It makes me wonder about Paris at the time and what it would have been like to walk the streets – and like I said, I wonder about the thoughts that were passing through the mind of the man as he stood having his shoes cleaned.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the centre of Paris was largely rebuilt by Georges-Eugène Haussmann under Napoleon III in a massive and controversial programme of urban renewal.

The Boulevard du Temple was largely demolished and remodelled, making way for the creation of the Boulevard du Prince Eugene.

Time moves everything on in the end.

his is believed to be the earliest photograph showing a living person